The Voluntary Carbon Market is one way of implementing carbon pricing in corporate operations. Its unit of account is the carbon credit, a transferable certificate that proves that a participant has achieved a surplus emission reduction or carbon removal equivalent to 1 ton of carbon dioxide, but has transferred the right to make green claims to another market participant in exchange for financial compensation. The players – whether they are standard owners, project developers, certifiers, green investors, or credit buyers – all enter the market voluntarily, so their activities go beyond regulations and national commitments, i.e., they achieve additional results in climate protection.

The market is undergoing significant change, with interrelated megatrends transforming the market's core product (technological carbon removal and nature-based carbon management), changing the way it is traded (offtake agreements), and are placing the emphasis on joint decarbonization (insetting) by participants in corporate value chains as a new strategic approach, legitimizing compensation both methodologically and legally in order to generate demand. Let us first look at the fundamental change that determines everything: the science-based transformation of the methodologies and best practices used, which together are capable of promoting a definitive departure from the stigma of the "farewell business."

The carbon market paradox

The VCM has been in existence for 20 years, but a breakthrough has not yet been achieved due to structural problems, which include the carbon market paradox, market fragmentation, and demand generation problems arising from a lack of legal legitimacy. The most important factor hindering the full development of the carbon market is that the VCM has fallen into a permanent credibility crisis due to the frequent lack of lasting additional effects, the leakage of results, and the resulting overcrediting that exceeds the actual climate protection results. As a result of the credibility crisis, the market has stalled over the past three years at an annual voluntary offset volume of around 200 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, with specific prices stuck at a low level, which does not allow for quality project development. This is the carbon market paradox, a practical example of the "chicken or egg" theoretical question.

The credibility crisis was brought to light by the Verra scandal that erupted in January 2023, in which it was revealed that up to 90 percent of the carbon credits from rainforest compensation projects in the global portfolio managed by the market's largest player could be phantom credits, i.e., not based on actual results. This threw mud on companies such as Disney, Shell, Apple, and VW, which had made particularly large commitments toward climate action and were big buyers of phantom credits. There were problems with both the methodology and the verification in the system, as a result of which Verra redesigned its standards and brought in external, independent experts for the most rigorous accreditations, as well as spearheading the renewal of the market, but its once excellent pedigree is gone and its market share is shrinking.

The carbon market paradox is a vicious circle, yet a long-term breakthrough is vital for the success of the green transition, but this requires a redefinition of the market. The cornerstone of the development of the VCM is therefore that offsetting becomes a legitimate tool, which requires a supply of quality carbon credits and demand support. Both are influenced by major international standard-setters, who steer the market with their recommendations. Moving forward will require shedding the stigma of the "farewell business," which has become a widespread pop culture narrative, so it will not be an easy ride.

Quality assurance of projects is critically important

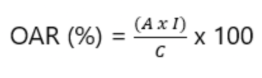

Analysts measure the quality of an emission using the Offset Achievement Ratio (OAR), where a high value indicates high integrity, i.e., excellent carbon credit quality, and a low value indicates the opposite. Based on a retrospective measurement, the OAR indicator shows what percentage of the carbon credits issued for a given green investment project as a project was realized. The OAR indicator is based on a retrospective measurement and shows what percentage of the carbon credits issued for a given green investment project were realized as additional emission reductions:

In the formula, "A" represents the extent to which the project is additional (its value falls between zero and one); "I" is the actual greenhouse gas emission reduction or absorption achieved by the project, measured in carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e); while "C" is the number of carbon credits issued on the basis of the project. The OAR indicator value is low if the project is not additional, or only slightly additional, and/or the measured emission reduction falls far short of the number of carbon credits issued. According to Allied Offsets' assessment, the vast majority of carbon credits generated based on traditional methodologies have an implicit OAR indicator of between 10 and 40 percent, meaning that the criticism is indeed justified.

In response to the lack of credibility, the supply side has embarked on a vigorous quality assurance program. Market self-regulation began in 2021 with the creation of the Integrity Council (ICVCM), which, after lengthy professional consultations, issued the Core Carbon Principles (CCP) in 2023, which require all organizations wishing to issue high-integrity carbon credits to have their emission standards accredited. The market expects the rapid spread of CCP-labelled carbon credits in the coming years, which has become an important megatrend. The first such certificates appeared in 2025, and their share is expected to be around 15 percent in 2026, while by 2030, the share of high-integrity carbon credits, with an OAR indicator above 80 percent, may exceed half of annual carbon credit issuances.

Offsetting is becoming a legitimate tool

The demand side is most influenced by the Science Based Target initiative (SBTi) corporate net zero emissions recommendation package, which is now voluntarily followed by nearly 10,000 large companies, and the number of followers is growing rapidly, despite the fact that legal enforcement is running out of steam worldwide. Climate action is clearly shifting towards voluntary actions. The latest set of recommendations for the above standard (SBTi v2.0) was published in 2025 and contains important new elements that point towards stimulating the VCM, i.e., generating demand, through the scientific recognition of responsible carbon footprint offsetting.

1. Timing expectations are becoming stricter. It sets out a specific timing expectation that, based on the corporate decarbonization strategy, responsibility for total emissions must be assumed by 2035 at the latest, while the net zero year must occur by 2050 at the latest as a target date.

2. It extends responsibility to the entire value chain. For ESG Scope 3 emissions (i.e., emissions generated in the value chain) exceeding 40% of total corporate emissions, detailed reporting of value chain emissions and setting reduction targets are mandatory. Since 70-90% of a company's total carbon footprint is often generated in the ecosystem, companies typically have to take responsibility for the emissions of the entire ecosystem.

3.Offsetting is becoming methodologically accepted. For objective efficiency reasons, the standard accepts that net zero must be achieved in the corporate ecosystem, at the national economic level, or even at the global economic level by the target date. This means that offsetting residual emissions that cannot be reasonably eliminated in the ESG scope 3 ecosystem with high-quality carbon credits becomes an integral part of corporate decarbonization strategy and is therefore methodologically legitimate. The recommendation sets continuously increasing specific offsetting requirements for companies that voluntarily pursue targets, sets limits for them, and also defines appropriate quality requirements for usable carbon credits.

4.It provides specific carbon pricing targets. In terms of carbon pricing, the standard technically allows for traditional offsetting, offtake agreements, internal carbon pricing, and the use of resulting reserves for green projects that comply with the taxonomy. It also sets specific target values for the carbon prices to be used, which are $20 per ton for "recognized" status and $80 for "leadership" status. Companies following the recommendation must publicly communicate the carbon price they apply, thereby increasing transparency and sending a positive signal that is so important in climate action. The recommendation thus gives a major boost to the positive rise in stagnant market prices, opening opportunities for project developers to launch larger-scale, high-quality green projects.